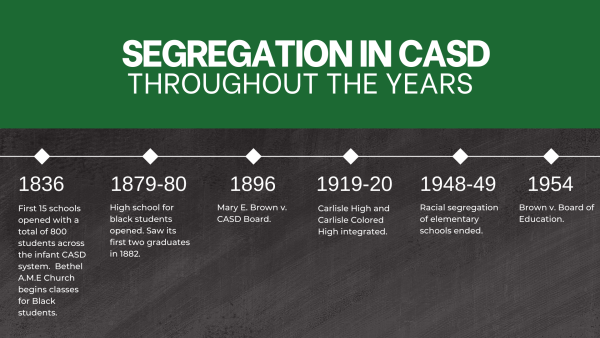

Nearly two centuries ago, Carlisle Area School District became the first chartered public school in Pennsylvania, providing classes to over 800 students across fifteen schools within the first year. These schools were small and separated by not only gender, but race as well. Of the fifteen buildings, not one was dedicated to the education of non-white students. Despite this blatant disparity, Carlisle’s Black community managed to coordinate, self-educate, and fight for equal academic opportunities, creating the basis for the diversity of present-day CASD.

At the heart of the district lies Carlisle High School, originally dubbed “Carlisle Senior High School” in the mid-20th century. Since then, CHS has expanded from one building to three, accommodating the growing Carlisle population. Its oldest building now bears the name of Emma Thompson McGowan in bold green letters above the entrance to the auditorium. To most students, “McGowan” is merely a maze of lockers and classrooms, presumably named after a person that used to be important enough to get a building named after them. In reality, Emma T. McGowan was a key figure in integrating CASD in the early 20th century and permanently changed the trajectory of education for the Black community in Carlisle.

“It’s All What You Make of It” was the Thompson family motto. They encouraged perseverance through hardships and never allowed themselves to be victims of circumstance.

Emma Louise Thompson was the first born in a family of 16 children to enslaved parents, Laura White Thompson and Charles (Caleb) Thompson, in 1876 in Winchester, Virginia. Soon after the Thirteenth Amendment, at the age of thirteen her family relocated to Carlisle in a wave of migration for formerly enslaved peoples. Her father, a skilled carpenter with a knack for communicating with horses, built a number of houses alongside his brother on Lincoln Street, which became the foundation for Carlisle’s Black community.

Being the oldest, Thompson was involved in housework and childcare very early on in her life. At the age of 14, her mother helped her to secure employment as a nursemaid where she made $1.50 per week. Her mother took every cent she earned and when she turned 21 in 1897, Thompson’s parents expected her to pay rent should she continue to live at home. In order to earn enough to pay rent, she secured a teaching position at the “Lincoln School for Colored” on Pitt Street earning $30 a month.

In 1898, Thompson met Rev. Osbourne Howard McGregor McGowan through her family’s church. Her father, charmed by the enigmatic reverend (who was 15 years his daughter’s senior), arranged a hasty marriage between them, and Emma Thompson became Emma T. McGowan. For roughly 20 years the couple moved around the Northeast, eventually landing in Detroit, Michigan, where the marriage met its end. Throughout their fifteen years together, the couple had six children, four of whom survived to adulthood. After the birth of the couple’s final child, Gladys, Emma filed for divorce in 1917 on the grounds of unspecified abuse.

Despite the tumultuous marriage, she decided to keep her former husband’s last name and soon after, her family helped her move back to Carlisle with her four children. Based on her previous teaching record and the school superintendent’s recommendation, McGowan was granted a provisional teaching certificate and began teaching again at the Lincoln School. She taught for a number of years before she completed her education certification in 1922 at the Cumberland Valley Normal School, which is now known as Shippensburg University.

As a teacher, McGowan was revered for her kindness, ambition, and unwavering faith. Many of her former students went on to become educators themselves, feeling her inspiration many years later. Her influence extended beyond her classroom walls into the entirety of Lincoln School and eventually, the CASD School Board. McGowan was a staunch advocate for desegregation who saw firsthand the disparities between the Lincoln School for Black students and the Wilson School for white students. As a result, she began working closely with the Young and Butcher families to integrate the two schools. She had already established connections with the two prominent Black families, as she graduated high school next to Mary Butcher in 1884. While the Butcher and Young families spearheaded the movement towards integration, McGowan took initiative from the schoolhouse, providing hundreds of Black students with an exceptional education despite funding and resource disparities. It wasn’t until 1919 that CASD desegregated officially at the high school level, and in 1948 at the elementary level.

As a teacher, McGowan was revered for her kindness, ambition, and unwavering faith. Many of her former students went on to become educators themselves, feeling her inspiration many years later. Her influence extended beyond her classroom walls into the entirety of Lincoln School and eventually, the CASD School Board. McGowan was a staunch advocate for desegregation who saw firsthand the disparities between the Lincoln School for Black students and the Wilson School for white students. As a result, she began working closely with the Young and Butcher families to integrate the two schools. She had already established connections with the two prominent Black families, as she graduated high school next to Mary Butcher in 1884. While the Butcher and Young families spearheaded the movement towards integration, McGowan took initiative from the schoolhouse, providing hundreds of Black students with an exceptional education despite funding and resource disparities. It wasn’t until 1919 that CASD desegregated officially at the high school level, and in 1948 at the elementary level.

After over 30 years of teaching, McGowan finally retired in 1943, just five years before she would’ve taught in an integrated classroom. She passed away at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement in 1966 when thousands of other schools across the country were desegregating and twelve years after the monumental Brown v. Board of Education decision.

In an effort to keep not only McGowan’s name alive, but her tenacity and spirit, Carlisle Historian Ruth E. Hodge successfully campaigned for the renaming of the West Building of CHS to honor McGowan in 2005.

All information and photos gathered from and credited to Cumberland County Historical Society, Gardner Digital Library, and Ruth E. Hodge. Periscope encourages readers to visit historicalsociety.com and gardnerlibrary.org to learn more about Carlisle’s Black history.

Mr. Wagner • Mar 5, 2024 at 1:20 pm

What an incredible piece of historiography! You should be proud of the research and story you have completed. Keep digging!!!

Amy B. Knapp • Feb 28, 2024 at 1:15 pm

Outstanding article! Thank you so much for writing this piece.